Photography and motion pictures, humanity's brilliantly stubborn endeavors to capture fleeting moments and immortalize them, have journeyed through extraordinary innovations and delightful absurdities. From shadowy smudges on pewter plates to digital selfies shared at warp speed, the path of photographic evolution has never lacked excitement, drama, or sheer human perseverance. So gather around—yes, even you at the back—and prepare yourself for a compelling, often humorous, always enlightening trek through the vivid timeline of photography and cinema.

What you're seeing here, sketched with typically understated brilliance by Leonardo da Vinci himself in 1515, is the camera obscura—a charmingly simple invention that proved Leonardo could conjure magic even without paintbrushes or marble. Essentially, it's just a darkened box with a tiny hole allowing outside scenes to mysteriously appear upside-down and reversed on an inner surface. Leonardo no doubt marveled at it, probably chuckling to himself at this playful trick of physics. Little did he know, he'd casually set the stage for all photography to come, long before anyone dreamed of capturing sunsets, birthday cakes, or the elusive perfect selfie.

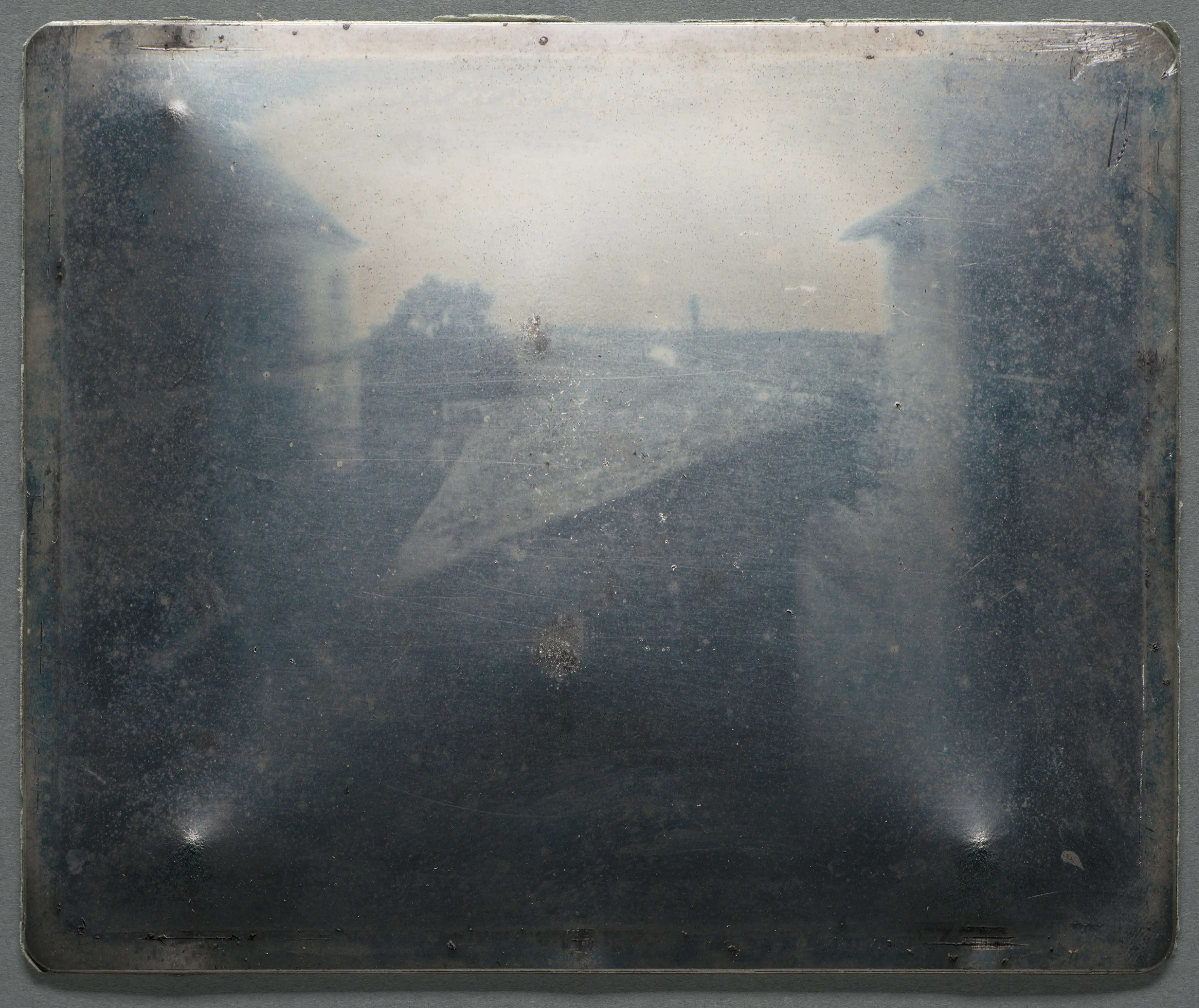

If you squint carefully, what you're looking at here—besides some intriguing blobs and shades—is the very first photograph ever taken. Created in 1826 by the patiently pioneering Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, this scene from his window at Le Gras required roughly eight full hours of exposure. Imagine that: an entire workday spent capturing one slightly blurry landscape. Niépce must have watched anxiously, hoping the clouds stayed away and his cat didn't knock the contraption over. The result might not look like much today, but it was revolutionary—this fuzzy rectangle launched an entire industry, changing forever how we record the world around us.

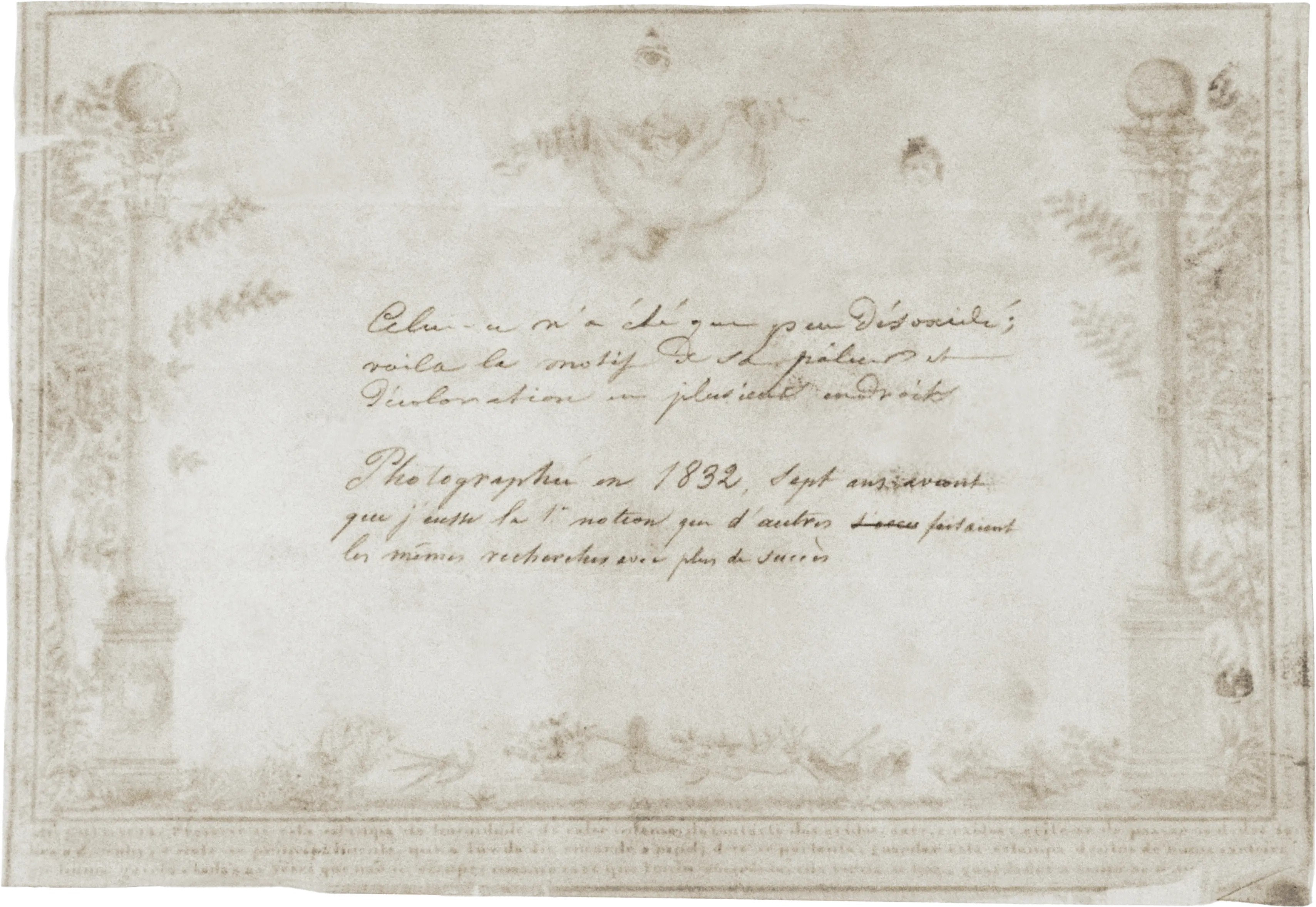

Here’s something rather astonishing: the world’s very first photocopy, created in 1833 by the quietly ingenious Hércules Florence, a Brazilian inventor whose name alone deserves applause. Long before office copiers turned reproducing documents into a mundane miracle, Florence was cleverly experimenting with sunlight, chemicals, and his remarkable persistence. This elegantly scripted diploma isn’t just beautifully crafted—it represents the very dawn of copying technology. You can almost picture Florence, quietly triumphant, marveling at how sunlight had just duplicated his handiwork, completely unaware he’d casually invented something that would one day become the heartbeat of every office break room.

Early Origins of Photography (Before 1839)

Long before photography captured selfies and profile pics, it began modestly with a simple phenomenon—the camera obscura, Latin for "dark room." Ancient philosophers marveled at how a tiny hole in a darkened chamber could project an inverted image from the outside world onto the opposite wall. Aristotle himself noted this curious effect during a solar eclipse, though presumably, he was more intrigued by the science than the artistic possibilities.

Fast forward to the Renaissance, where artists discovered they could trace incredibly accurate landscapes and portraits from these projected images, revolutionizing painting and perspective. Leonardo da Vinci, Renaissance master and relentless inventor, sketched elaborate diagrams of the camera obscura, though sadly never took the logical next step—capturing the image permanently.

Centuries passed with fleeting projections and frustrated inventors. Thomas Wedgwood (1771–1805), son of the pottery legend Josiah Wedgwood, experimented boldly with silver nitrate-coated paper, capturing ghostly images of leaves and insects. Unfortunately, these pioneering photographs stubbornly vanished faster than a fart from a fly.

Enter Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833), a patient French inventor whose relentless experiments ultimately bore fruit. In 1826, Niépce succeeded in creating the world's first permanent photograph, known as a heliograph. After an exhaustive eight-hour exposure from his upstairs window, Niépce managed to preserve a hazy yet remarkable image, aptly named "View from the Window at Le Gras." While this photograph was not particularly glamorous—featuring mostly rooftops and blurry trees—it proved one crucial point: capturing images was indeed possible.

In England, another pioneer, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), independently experimented with photogenic drawing, a process using paper soaked in silver chloride. Talbot's early methods produced delicate silhouettes and shadows but, like Wedgwood, initially failed to fix images permanently. Talbot persisted, however, eventually introducing a revolutionary system: the calotype, allowing negatives to produce endless copies.

Meanwhile, Hércules Florence (1804–1879) in Brazil was also discovering photographic methods. Despite significant breakthroughs—including developing stable images on paper—Florence remained largely unknown internationally, possibly because Brazil offered more enticing distractions than endless hours trapped in a darkroom.

Thus, by the early 1830s, photography teetered on the brink of breakthrough, with numerous inventors poised across continents. But one man would soon thrust this fascinating invention firmly into the public spotlight.

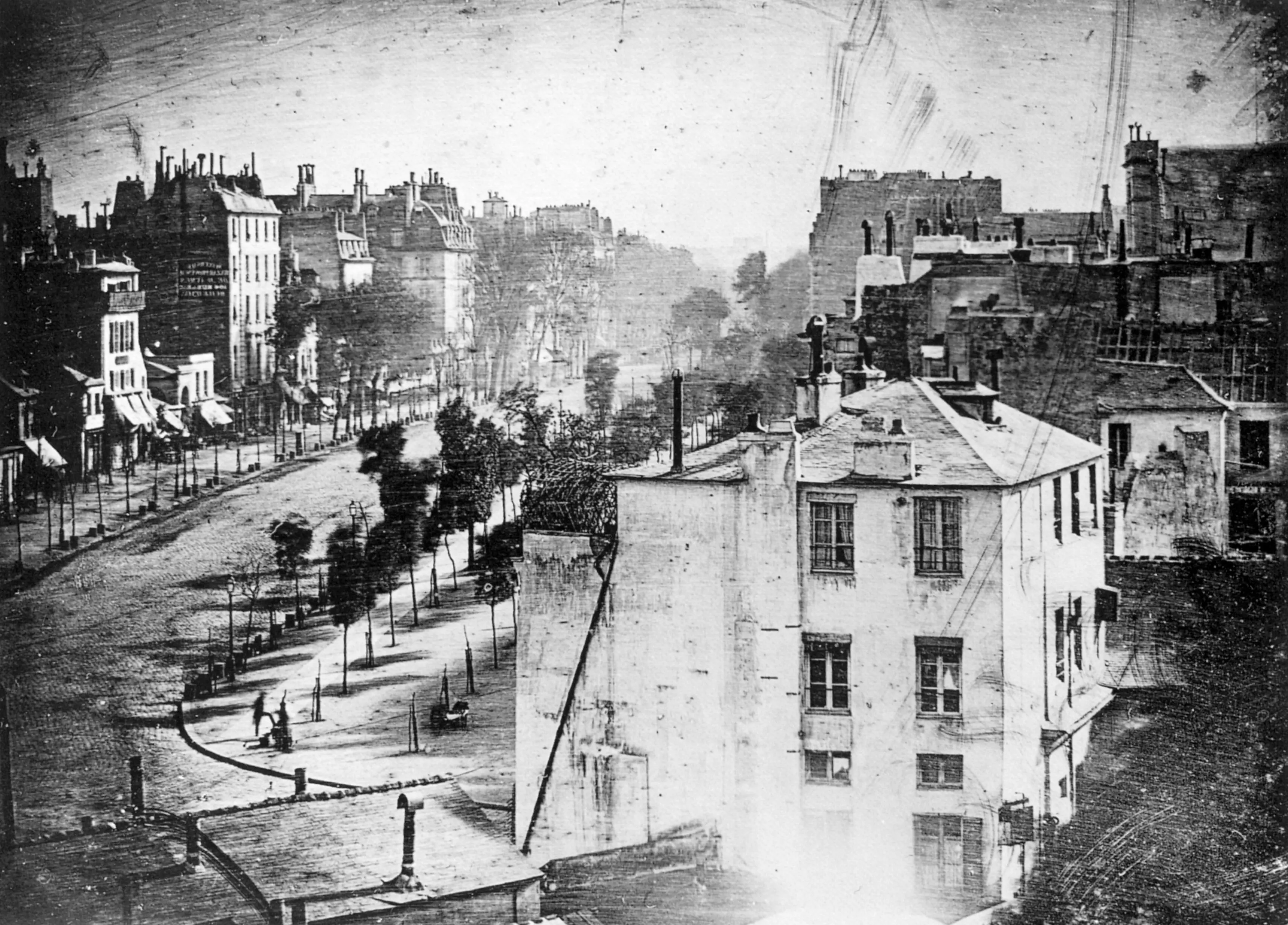

At first glance, this looks like a suspiciously deserted Parisian boulevard—a scene straight from a post-apocalyptic film—but in fact, this 1838 daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre marks a charming photographic first: the earliest known photograph featuring a human being. Look closely in the bottom left corner, and you’ll spot a lone figure patiently having his boots polished. Due to the long exposure time required, the bustling traffic and busy pedestrians vanished like ghosts, leaving only this oblivious gentleman immortalized forever. One wonders if he ever discovered his unintended fame—or simply wandered off into history, shiny boots and all, blissfully unaware of his pioneering role.

Meet Robert Cornelius, who in 1839 took this strikingly modern-looking self-portrait—making him, astonishingly, the inventor of the photographic selfie nearly two centuries before the term existed. With his tousled hair, intense stare, and casual confidence, Cornelius managed to perfectly capture that universally recognized selfie pose: the “I wonder if this thing is actually working” expression. The photograph required a lengthy exposure, meaning Robert had to hold perfectly still, probably pondering the wisdom of his experiment. Little did he know, he'd just casually invented the timeless art of self-documentation, minus the duck face and hashtags.

Daguerreotypes and Calotypes (1839–1850s)

Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), a French artist and showman, burst onto the scene in 1839, dazzling audiences worldwide with the daguerreotype. Daguerre's method involved a polished silver-coated copper plate sensitized with iodine fumes, creating exquisitely detailed images after relatively short exposures—initially minutes rather than hours. These images, clear and sharply defined, appeared almost magical. Although subjects had to endure uncomfortable stillness, often held in place by clamps or hidden braces, the astonishing clarity of the resulting portraits thrilled Victorians eager to immortalize their somber faces.

Daguerreotypes, however, had one significant drawback: each was unique and irreproducible. Enter William Henry Fox Talbot again, who, almost simultaneously, presented his calotype process. Talbot's technique used paper negatives, from which endless soft, sepia-toned prints could be made—ideal for mass-producing and sharing, albeit slightly blurry, images.

Meanwhile, botanist Anna Atkins (1799–1871) innovatively utilized cyanotype photography for scientific illustration. In 1843, Atkins published the first-ever photographic book, "Photographs of British Algae," showcasing delicate blue-and-white silhouettes of plants. Her beautiful yet esoteric images likely captivated botanists and bewildered dinner guests alike.

In France, photographer Hippolyte Bayard (1801–1887), resentful that Daguerre overshadowed his simultaneous innovations, staged the first photographic protest. He theatrically portrayed himself as a drowned man, lamenting his unnoticed genius—a wry joke proving photographers have always had a flair for the dramatic.

Thus, the daguerreotype and calotype set the stage for photography’s explosive growth, expanding rapidly across continents and transforming society’s relationship with image-making forever.

Here, wonderfully, is photography’s first-ever act of protest. Hippolyte Bayard, feeling rather miffed at being overlooked by history in favor of Louis Daguerre, posed himself dramatically as a drowned man in 1840. Complete with artful nudity, a solemn expression, and a carefully arranged straw hat, Bayard created a self-portrait captioned with a wryly sarcastic note lamenting his ignored genius. It’s equal parts tragic, humorous, and entirely French—a clever reminder that even at the dawn of photography, image-makers knew how to use their medium not just to capture reality, but to stage delightful, pointed fictions as well.

Despite its rather poetic title, "Valley of the Shadow of Death," taken by Roger Fenton in 1855, is a quiet, eerily empty stretch of Crimean landscape littered ominously with cannonballs. This was one of the first war photographs ever made, and it's all the more haunting for what it doesn't show—no soldiers, no explosions, just silent remnants of violence scattered on a lonely road. Fenton lugged heavy camera equipment through conflict zones, somehow capturing a moment of chilling serenity amidst chaos. One imagines him carefully positioning the camera, perhaps wondering, as he adjusted settings, about the strange absurdity of photographing war—an act both courageous and curiously detached.

Here's Billy the Kid, captured in an iconic tintype portrait around 1879–1880 at Fort Sumner. The tintype was essentially the photographic world's answer to fast food—quick, affordable, and surprisingly durable. Made by coating a thin sheet of iron with chemicals and snapping the photo while still wet, tintypes could be ready in minutes, perfect for fairs, carnivals, and roadside studios. This one remains the only authenticated image of the famous outlaw, displaying a casually confident young man, rifle at hand, and hat slightly askew. Little did Billy realize this single piece of metal would become his lasting legacy, ensuring his face would be remembered long after the dust had settled.

Wet Plates and Global Expansion (1850s–1860s)

The 1850s saw photography accelerate with Frederick Scott Archer’s (1813–1857) wet collodion process, which combined clarity and reproducibility. Glass plates coated with a sticky chemical mixture allowed photographers to capture incredibly sharp images within seconds rather than minutes, although the plates had to remain wet throughout exposure and development.

This inconvenience led photographers to lug portable darkrooms everywhere—from battlefields to bustling cities—capturing powerful imagery of life and conflict. Roger Fenton (1819–1869), for example, brought haunting images of the Crimean War back to Europe, forever changing perceptions of war. Mathew Brady’s (1822–1896) team captured vivid, sometimes horrifying photographs of the American Civil War, revealing its stark realities to distant spectators.

Wet plates also birthed popular, affordable portrait formats such as ambrotypes (glass positives viewed against a dark backing) and tintypes (images on thin lacquered iron). These became staples at fairs and carnivals, democratizing photography and making instant portraits accessible to the masses, much like today’s photo booths.

This period also saw remarkable global expansion. Felix Nadar (1820–1910) captured the world’s first aerial photographs from hot-air balloons, pioneering perspectives previously unimagined. In India, photographer Lala Deen Dayal (1844–1905) captured stunning portraits of royalty and common folk alike, demonstrating photography’s universal appeal and ability to transcend cultural barriers.

Thus, by the late 1860s, photography had firmly entrenched itself globally, influencing journalism, art, and even daily life, preparing the stage for further revolutionary innovations in capturing reality and imagination.

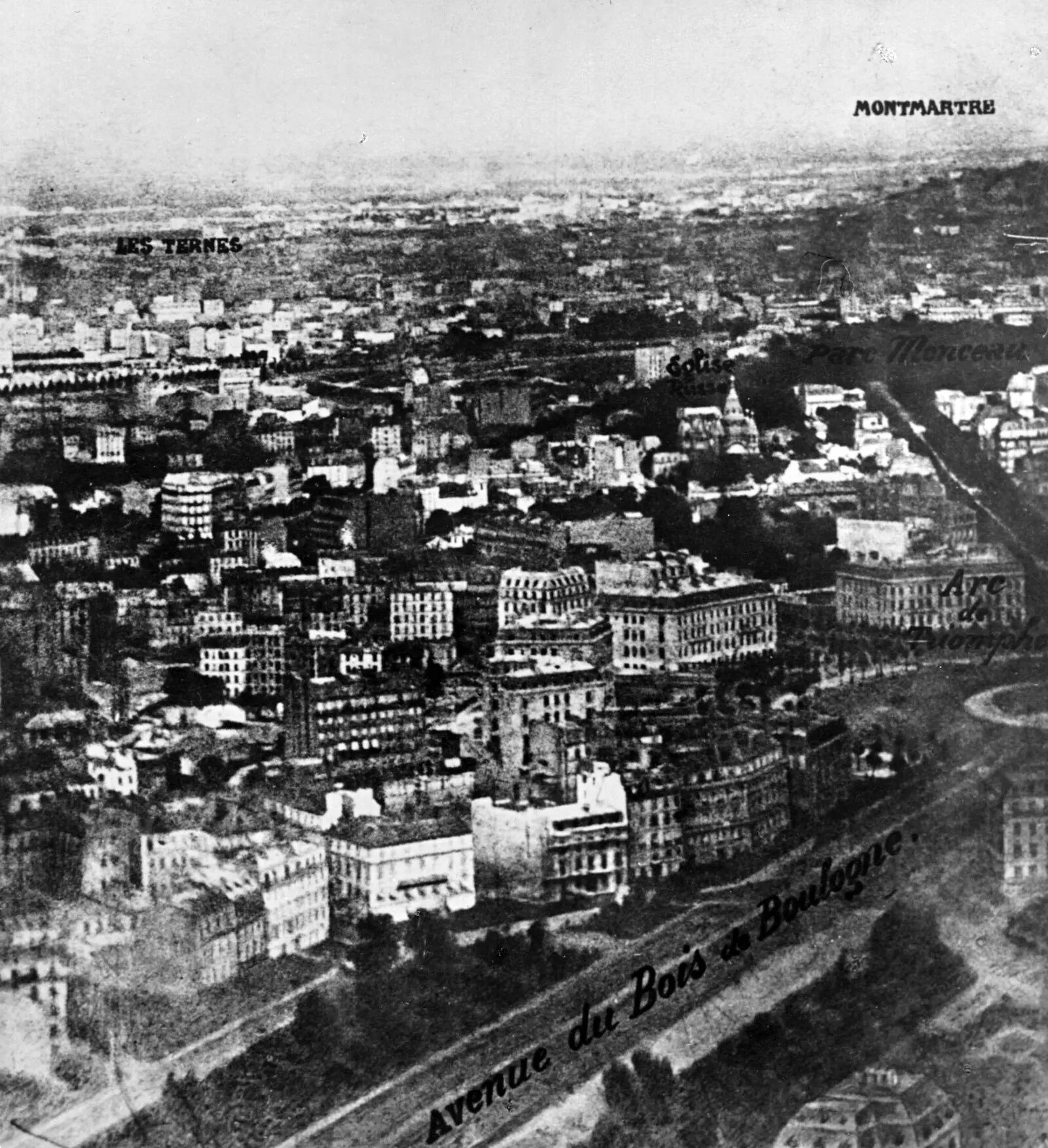

This extraordinary photograph, taken in 1858, was captured by Félix Nadar—arguably one of history's bravest photographers and certainly among its most innovative. Hovering above Paris in a precarious hot-air balloon, Nadar managed to snap the world's first aerial photograph of the city, giving Parisians a bird's-eye view they had previously only dreamed of. Imagine Nadar, balancing a cumbersome camera hundreds of feet above the boulevards, probably cursing gently as the balloon swayed. It's a testament not only to his courage but also to humanity's eternal desire to see the familiar world from astonishing new angles—preferably without falling out of the sky.

Meet the original Kodak camera, the ingenious little gadget that arrived in the summer of 1888 and immediately turned photography into something delightfully easy. Before its debut, taking a picture required lugging around heavy equipment and mastering complex chemistry. Kodak cheerfully swept away these inconveniences with its clever slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest." Loaded with enough film for 100 photos, this charming wooden box allowed everyday people to effortlessly capture life's fleeting moments—family picnics, seaside holidays, and children squirming impatiently. It wasn't merely a camera; it was the birth of modern snapshot culture, changing the way humanity preserved memories forever.

These quaint cardboard boxes hold rolls of Kodak film from 1888 and 1889, tiny historical treasures that revolutionized photography almost overnight. Before these tidy little packages appeared, taking photographs was a complicated, messy affair involving fragile glass plates and delicate chemicals. Kodak's neatly rolled film was a stroke of genius—compact, portable, and user-friendly. Suddenly, photography wasn't just for professionals or the obsessively dedicated amateur. Everyone could document their everyday adventures and misadventures—though, one suspects, even Kodak couldn't have predicted our modern enthusiasm for photographing every latte, lunch, and kitten we encounter.

Dry Plates and the Kodak Revolution (1870s–1890s)

As photography continued its relentless march into practicality, Richard Leach Maddox (1816–1902), an English physician with perhaps too much free time, invented the gelatin dry plate in 1871. Unlike wet plates, Maddox’s method allowed photographers to prepare plates well in advance, freeing them from cumbersome portable darkrooms. Imagine the collective sigh of relief from photographers who could now capture images without scrambling to coat and develop glass plates on the spot. Maddox’s invention drastically reduced exposure times and simplified photography, sparking a new wave of accessibility.

By the late 1870s, the gelatin dry plate became commercially viable, and factories began mass-producing these convenient photographic plates. This newfound ease and efficiency opened photography to amateur enthusiasts, allowing ordinary individuals—not just skilled professionals—to experiment and document their world.

Enter George Eastman (1854–1932), an entrepreneurial visionary who recognized photography's vast commercial potential. In 1888, Eastman introduced the revolutionary Kodak camera, a handheld, user-friendly box preloaded with roll film capable of capturing 100 snapshots. His famously catchy slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest", accurately summarized his ingenious business model: customers simply mailed their entire cameras to Kodak, which processed the film, printed the images, and returned the camera reloaded. This simple concept democratized photography, forever transforming it from a specialized craft into an accessible pastime for millions.

Eastman further simplified photographic processes by introducing flexible, transparent film in 1889, significantly lighter and less fragile than glass plates. His innovations not only revolutionized still photography but also laid foundational technology for emerging motion picture industries. The roll film format became an essential stepping stone toward capturing sequential images, paving the way for filmmakers who would soon harness the illusion of motion to entertain, educate, and astonish global audiences.

During this era, pioneering photographers also captured remarkable scenes previously beyond reach. Jacob Riis (1849–1914), a Danish-American journalist, utilized flash photography to reveal the stark realities of urban poverty, bringing awareness and spurring social reform. His groundbreaking work highlighted photography's power as a social tool, capable of driving change by visually confronting viewers with uncomfortable truths.

Thus, by the close of the 19th century, photography had rapidly evolved from complicated and cumbersome beginnings into a user-friendly medium that anyone could embrace. The Kodak revolution sparked not just technological advancements but profound social impacts, changing forever how people perceived and preserved their personal histories and collective experiences.

These delightful circular snapshots, captured on Kodak's earliest roll-film cameras around 1888-1889, charmingly illustrate Victorians discovering leisure photography. From a stylish woman enjoying a breezy boat ride and gentlemen leisurely seated on a promenade, to playful children exploring sandy beaches and a quiet moment with a book, these candid images portray everyday life with remarkable intimacy. Kodak's unique circular format wasn't just practical—it imparted an air of friendly informality, perfectly complementing the gentle absurdity and everyday beauty of ordinary moments, captured spontaneously by photographers newly empowered by simple, handheld cameras.

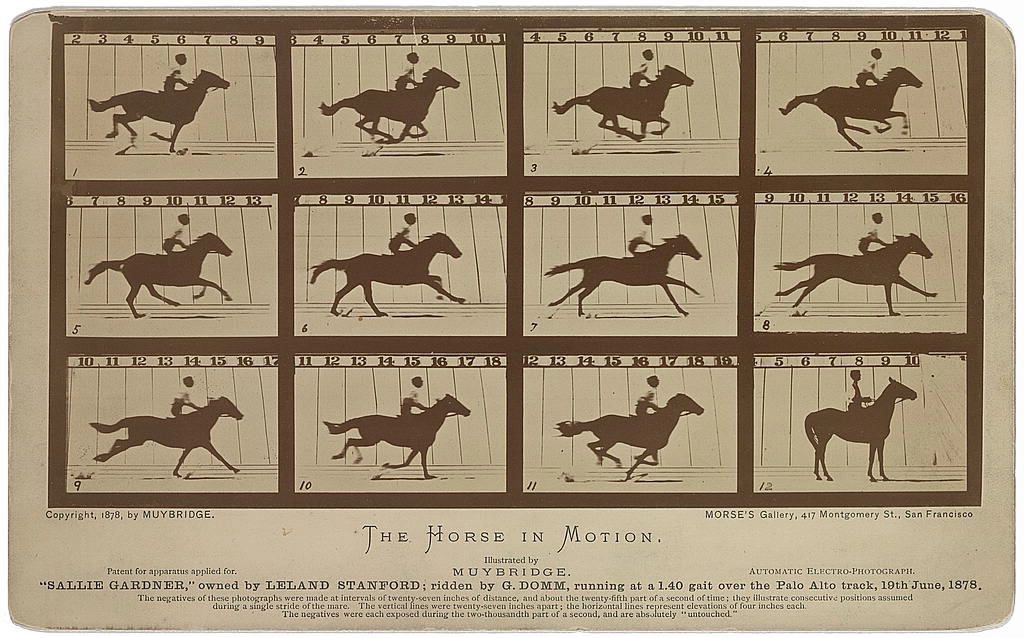

This mesmerizing sequence, famously titled "The Horse in Motion," is Eadweard Muybridge's remarkable contribution from 1878—proof that all four hooves of a galloping horse do indeed leave the ground simultaneously, settling a popular wager of the time. Muybridge cleverly lined up multiple cameras along a racetrack to capture these rapid-fire frames, inadvertently giving birth to motion photography. Ironically, he wasn't aiming to invent movies; he simply wanted to resolve a friendly argument about equine movement. Yet, in capturing this fleeting instant, Muybridge accidentally laid the groundwork for cinema itself. Not bad for a day's work—and certainly more interesting than most wagers.

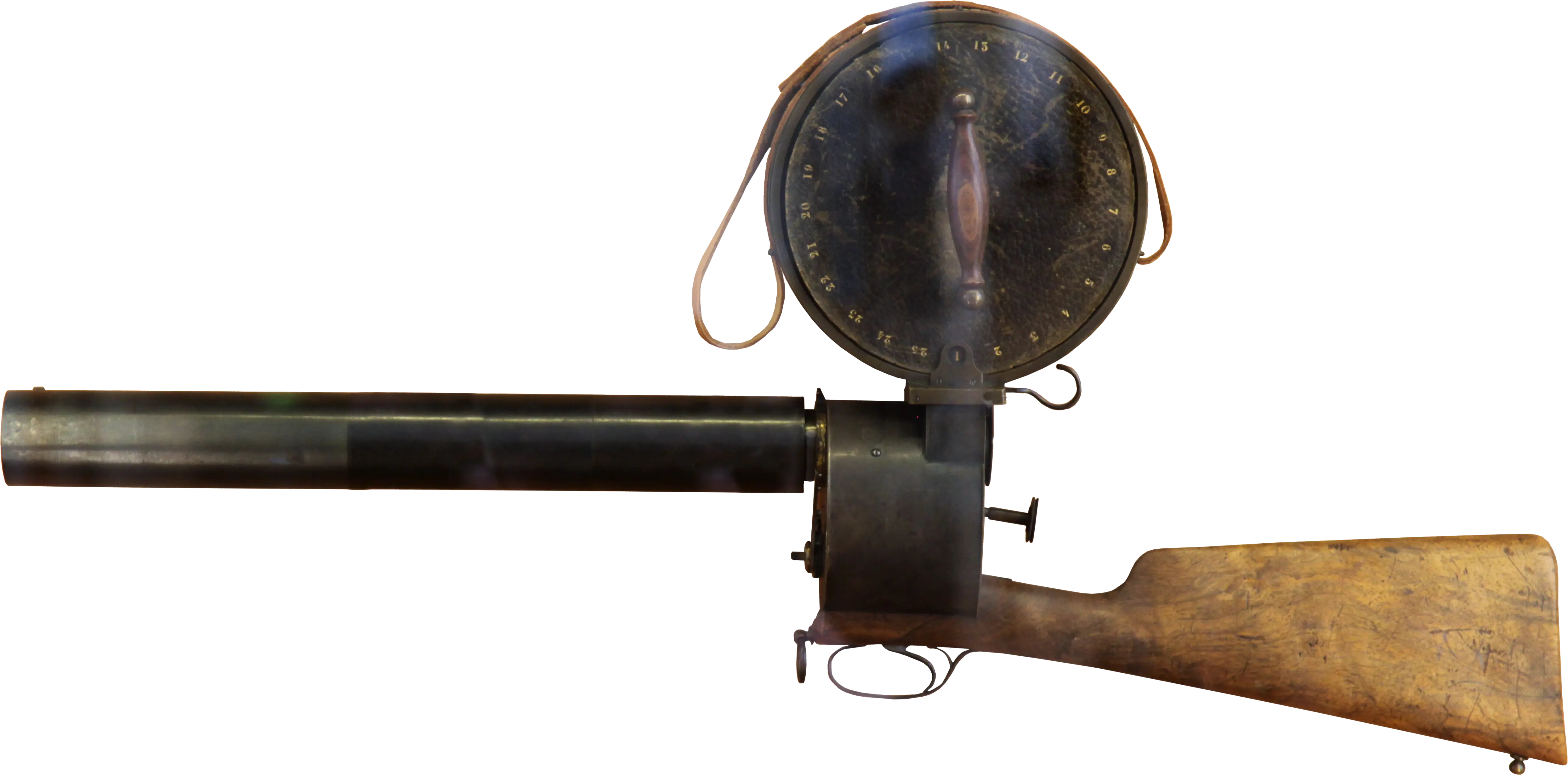

This curious-looking contraption is Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotographic gun from 1882—a brilliant, if slightly alarming, device used to capture motion through rapid sequential photographs. Marey, a dedicated scientist fascinated by animal and human locomotion, ingeniously adapted this "photographic rifle" to shoot multiple frames per second, thus freezing motion and allowing careful analysis of movements previously invisible to the naked eye. Imagine Marey, lurking behind bushes aiming this photographic gun at startled pigeons, thoroughly unnerving passersby who no doubt wondered if science had finally taken its experiments a step too far. Yet, in doing so, Marey helped pave the way not just for film, but also for modern biomechanics—quite the productive day’s hunting.

Moving Images: Early Motion Studies (1870s–1880s)

The late 19th century was not merely content with capturing still moments; it yearned to capture motion itself. The possibility of photographic sequences sparked fierce debate among scientists, artists, and even gamblers. Enter Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), a colorful English photographer whose eccentricity rivaled his technical genius. In 1878, Muybridge famously tackled the mystery of whether all four of a horse's hooves left the ground simultaneously during a gallop—a topic hotly debated among horse enthusiasts, scientists, and wagering gentlemen alike.

Funded by railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, Muybridge arranged a series of twelve cameras along a racetrack, each triggered by a thread as the galloping horse passed by. The resulting sequence of photographs conclusively proved that horses do indeed briefly "fly" mid-gallop. Muybridge didn't stop there—he developed the zoopraxiscope, an early motion-picture device that projected his sequential photographs onto a rotating disk, creating the mesmerizing illusion of movement and astonishing audiences worldwide.

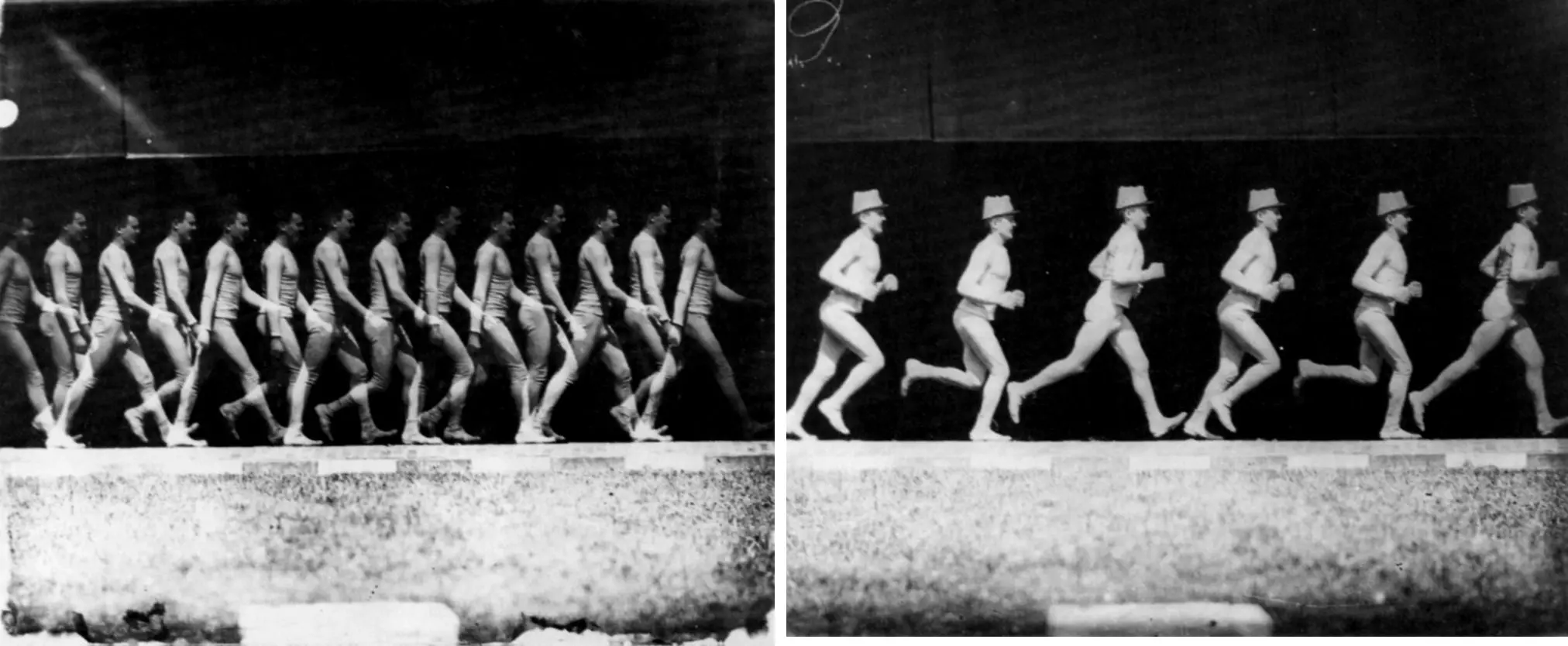

Meanwhile, Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904), a meticulous French physiologist, approached motion studies from a scientific perspective. He invented the chronophotographic gun, capable of capturing twelve consecutive frames per second onto a single photographic plate. Marey used his invention to study animals and athletes, breaking down movements into precise photographic sequences for detailed analysis. His pioneering work laid critical groundwork for the science of biomechanics and significantly influenced the development of cinema technology.

These remarkable breakthroughs not only demonstrated photography's potential to capture motion but also paved the way for a new storytelling medium—motion pictures—that would soon captivate global audiences and revolutionize entertainment, culture, and communication. Thus, the 1870s and 1880s became crucial decades, bridging the gap between still photography and the imminent birth of cinema.

Here are Étienne-Jules Marey's extraordinary chronophotographs, capturing the intricate motion of a man walking and then running—complete with rather delightful hats. Marey, a keen scientist fascinated by movement, used his photographic methods to dissect the subtleties of human locomotion in ways previously unseen. These ghostly sequences, created in the 1880s, are more than scientific curiosity—they inadvertently became some of the earliest steps towards modern filmmaking and animation. And, if nothing else, they offer reassuring evidence that humanity has always struggled to look completely dignified while jogging.

This brief clip from "Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat," filmed in 1895 by the pioneering Lumière brothers, famously startled its first audiences into ducking for cover—though historians debate whether spectators really ran screaming from the room. Nonetheless, the footage represents cinema's magical beginnings: a train gently pulling into a French station, passengers stepping onto the platform, and unwittingly becoming among the first film stars in history. It seems quaint today, but back then, this train was blockbuster entertainment.

This delightful and slightly surreal scene comes from Georges Méliès' iconic 1902 film, "A Trip to the Moon"—cinema's earliest science fiction blockbuster. With whimsical storytelling and dazzling special effects (for the time, of course), Méliès sent audiences on a fantastic voyage, complete with astronomers in suits and top hats, and the unforgettable moon-face grimacing after an unfortunate rocket collision. The film's charm lies in its playful creativity and gentle absurdity, showing the boundless imagination that the early pioneers brought to filmmaking.

Here's the marvelous Buster Keaton, demonstrating his legendary talent for impeccable timing and understated chaos in this classic clip from his 1922 silent comedy "Cops." Keaton, famously stone-faced, turns a simple street chase into a meticulously choreographed ballet of slapstick humor and escalating mayhem.

Birth of Cinema and Silent Film (1890s–1920s)

As the 19th century drew to a close, the tantalizing promise of capturing and displaying moving images transitioned from scientific curiosity to mass entertainment. Thomas Edison (1847–1931), the tireless American inventor whose numerous creations shaped modern life, and his talented assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson (1860–1935), developed the kinetograph, the world's first motion picture camera. Accompanying it was the kinetoscope, an individual viewing device that allowed people to peer into a box and witness brief, flickering snippets of life, from boxing matches to ballet performances.

However, the kinetoscope’s limitation—its solitary viewing experience—left room for improvement. Enter the Lumière brothers, Auguste (1862–1954) and Louis (1864–1948), innovative French inventors who transformed cinema into a communal experience. In December 1895, the Lumière brothers presented their Cinématographe, an ingenious invention serving as camera, projector, and printer, to a fascinated Parisian audience. The short films projected onto a large screen—from the simple "Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory" to the legendary "Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat"—mesmerized viewers and, according to legend, even frightened some audience members into believing the locomotive might burst through the screen.

The Lumière’s public screenings ignited a global cinematic revolution. Filmmakers rapidly discovered cinema’s storytelling potential, transforming simple recordings of daily life into narrative-driven, imaginative spectacles. Georges Méliès (1861–1938), a magician-turned-filmmaker, quickly recognized cinema’s capacity for fantasy. His iconic 1902 film, "A Trip to the Moon," combined elaborate sets, innovative special effects, and whimsical storytelling, enchanting audiences and demonstrating film's unlimited imaginative potential.

Silent cinema quickly evolved into a thriving global industry. Studios emerged across Europe and America, producing films spanning diverse genres—from slapstick comedy and romantic drama to epic historical narratives and gripping adventures. Pioneering actors like Charlie Chaplin (1889–1977), Mary Pickford (1892–1979), and Buster Keaton (1895–1966) captivated audiences worldwide, becoming the first international superstars without uttering a single audible word. Their physical expressiveness and compelling screen presence communicated stories universally, transcending language barriers.

Filmmaking techniques rapidly advanced, introducing sophisticated narrative structures, cinematic editing styles, and groundbreaking visual effects. D.W. Griffith’s controversial yet technically groundbreaking 1915 film, "The Birth of a Nation," revolutionized storytelling methods with innovative cross-cutting and camera movements, influencing countless filmmakers despite its divisive historical impact.

Silent films also saw significant global diversification. In Germany, directors such as Fritz Lang (1890–1976) and F.W. Murnau (1888–1931) pioneered expressionist cinema, creating atmospheric, visually stunning masterpieces like "Metropolis" and "Nosferatu." Soviet filmmakers, including Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948), revolutionized cinematic editing through "montage," a dynamic method that intensified emotional and political narratives. In Japan, filmmakers like Yasujiro Ozu (1903–1963) began crafting stories deeply rooted in local culture yet universally poignant, demonstrating cinema’s cross-cultural storytelling power.

Thus, by the 1920s, cinema had blossomed into a powerful cultural force, shaping global consciousness, entertainment, and artistic expression. Audiences everywhere eagerly gathered in elaborate movie palaces to witness silent films, forever altering human entertainment and setting the stage for cinema’s next groundbreaking transformation—the advent of sound.

This vibrant clip is from the 1922 silent film The Toll of the Sea, directed by Chester M. Franklin. It holds the distinction of being one of Hollywood's first color features, beautifully captured through the Technicolor two-color process. While earlier cinema relied on tinted or hand-painted scenes, Technicolor brought lush and authentic hues to moviegoers for the first time, providing audiences with a dazzling visual feast. Here, the vibrant reds and greens seem to practically leap off the screen, giving this poignant drama an emotional resonance that black-and-white films could only dream of. Watching this now, it's easy to understand how audiences were utterly captivated—colors so vibrant you could almost smell the flowers.

This impressively bulky contraption is a genuine Technicolor three-strip camera from Hollywood's golden age—circa 1930s-1940s. While it may look more like industrial machinery than filmmaking equipment, this cumbersome device revolutionized cinema by capturing vivid, lifelike colors on three separate film strips simultaneously. Operated by specially trained technicians (who presumably had very strong backs), it transformed drab studio sets into lush, mesmerizing worlds, creating film classics like The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Its complexity and sheer size often baffled actors, annoyed directors, and thrilled audiences—proving once again that great art sometimes requires remarkably unwieldy technology.

Here's Donald Duck in the surprisingly subversive 1943 wartime cartoon Der Fuehrer's Face, directed by Jack Kinney for Walt Disney Studios. Originally crafted as anti-Nazi propaganda, it was both hilarious and biting, lampooning Hitler's oppressive regime through the hapless adventures of Donald, who finds himself trapped in a nightmarish world of marching bands and aggressive breakfast foods shaped suspiciously like swastikas. It ultimately won an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film—perhaps proving that nothing undermines authoritarianism quite as effectively as ridicule served up by an irritable cartoon duck.

The Talkies and Technicolor (1920s–1940s)

The late 1920s introduced cinema's greatest revolution yet—the integration of sound. While silent films had captivated global audiences for decades, the desire to synchronize sound with moving images was persistent. Warner Brothers, a relatively small Hollywood studio at the time, risked substantial investment to produce the pioneering "talking picture," "The Jazz Singer" (1927). Starring Al Jolson, this groundbreaking film featured synchronized singing and limited dialogue sequences, electrifying audiences and reshaping the cinematic landscape overnight. Although it contained only a handful of synchronized scenes, audiences were stunned and fascinated by hearing an actor's voice matched precisely with lip movements on screen for the first time.

This innovation marked the rapid decline of silent cinema. Studios scrambled to adopt sound, transforming production methods dramatically. Actors whose silent careers flourished faced unprecedented challenges; clear diction, vocal appeal, and adaptability to new performance styles became essential. Many prominent silent film stars struggled to transition successfully to sound, while others, such as Greta Garbo (1905–1990) and Clark Gable (1901–1960), leveraged sound to bolster their careers and stardom.

Simultaneously, cinema embraced another transformative technological leap—Technicolor. While various attempts at color filmmaking existed previously, Technicolor introduced the most vibrant, practical, and visually breathtaking method yet. Developed by Herbert Kalmus (1881–1963) and Daniel Comstock (1883–1970), Technicolor employed a sophisticated three-strip process, capturing scenes simultaneously through three different colored filters—red, green, and blue—producing astonishingly vivid and rich color imagery on screen.

Technicolor's debut profoundly reshaped cinematic storytelling. The initial successes, such as Disney's enchanting "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937), showcased the medium's potential, mesmerizing audiences with dazzling colors and imaginative visuals. Hollywood quickly recognized Technicolor's potential, adopting it widely for musicals, epics, and prestige pictures. Films like "Gone with the Wind" (1939) and "The Wizard of Oz" (1939) utilized Technicolor masterfully, turning vibrant color cinematography into cinematic spectacle, amplifying emotional storytelling, and cementing these films as timeless classics.

Meanwhile, global political turmoil and World War II significantly influenced cinematic production and themes. Filmmakers worldwide responded to wartime realities, creating propaganda films to bolster morale, patriotic war dramas to inspire audiences, and insightful documentaries illuminating wartime struggles and heroics. Filmmaking also served as historical documentation, capturing crucial events, battles, and personalities.

Cinema's power expanded globally, serving political and cultural purposes beyond mere entertainment. Germany, under Nazi rule, exploited cinema as a potent propaganda tool, while filmmakers in the United States and Britain produced films reinforcing democratic ideals and unity against fascism. Soviet filmmakers created powerful propaganda pieces emphasizing communal sacrifice and resilience against invasions, demonstrating cinema's influential role in shaping public opinion and morale during pivotal historical moments.

Thus, the period spanning the 1920s to the 1940s saw cinema transformed profoundly by sound and color. These revolutionary advancements reshaped filmmaking practices, redefined storytelling methods, and profoundly altered audience experiences, firmly establishing cinema as an indispensable cultural force worldwide, capable of entertaining, educating, and influencing global society profoundly.

This strikingly crisp Kodachrome photograph of London, taken by Chalmers Butterfield around 1949, captures post-war life with astonishing clarity and vibrancy. Kodachrome film, beloved for its rich, enduring colors, gave everyday scenes like this—buses bustling along damp streets, gentlemen in neatly pressed suits—a cinematic quality that still fascinates. Unlike previous color processes, which faded faster than memories of last year’s vacation, Kodachrome promised vivid, true-to-life images that lasted decades. It transformed how we remember the past, preserving moments with such precision that you half-expect the pedestrians to resume their journeys at any moment.

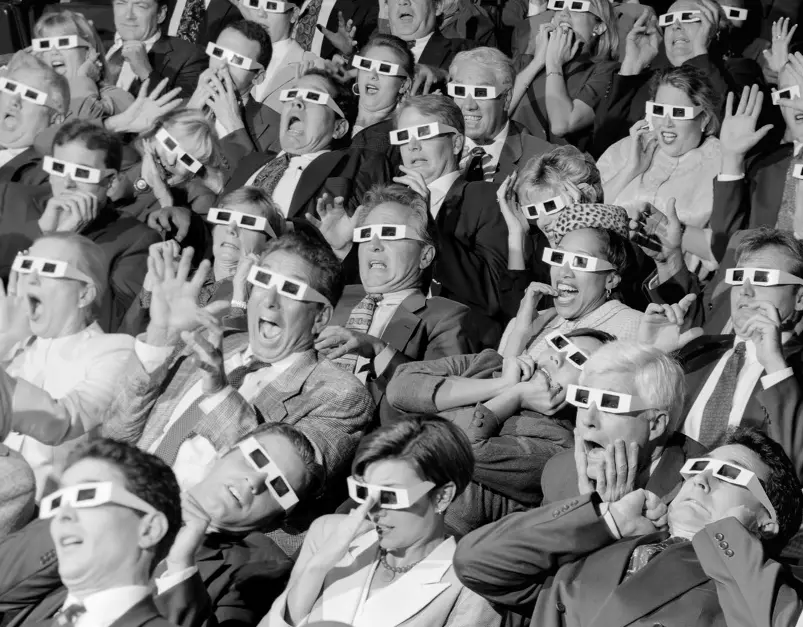

Ah, the 1950s—when America was convinced the future would come with flying cars, personal robots, and, evidently, movies that lunged right at your face. This glorious image captures a theater full of thrilled spectators donning 3D glasses, reacting en masse to something presumably leaping off the screen—possibly a monster, spaceship, or overly enthusiastic pie fight. The brief golden age of 3D cinema was a gimmicky but earnest attempt to re-lure viewers away from their newfangled televisions. And while the technology back then often produced more headache than immersion, the idea that movies could momentarily invade your personal space was simply irresistible. It was, quite literally, entertainment in your face.

Here, side by side, we see the remarkable cultural influence of Kodachrome film: Steve McCurry’s legendary "Afghan Girl" from the cover of National Geographic (June 1985), and the poster for the 2017 film Kodachrome. One is perhaps the most famous magazine cover of all time—a portrait so striking that it etched itself into global memory. The other is a cinematic tribute to the film that made such iconic images possible. Kodachrome, celebrated for its extraordinary color fidelity, became more than film; it was a symbol of nostalgia, adventure, and visual storytelling. Decades later, its impact continues to resonate, from powerful photographic journalism to heartfelt Hollywood narratives.

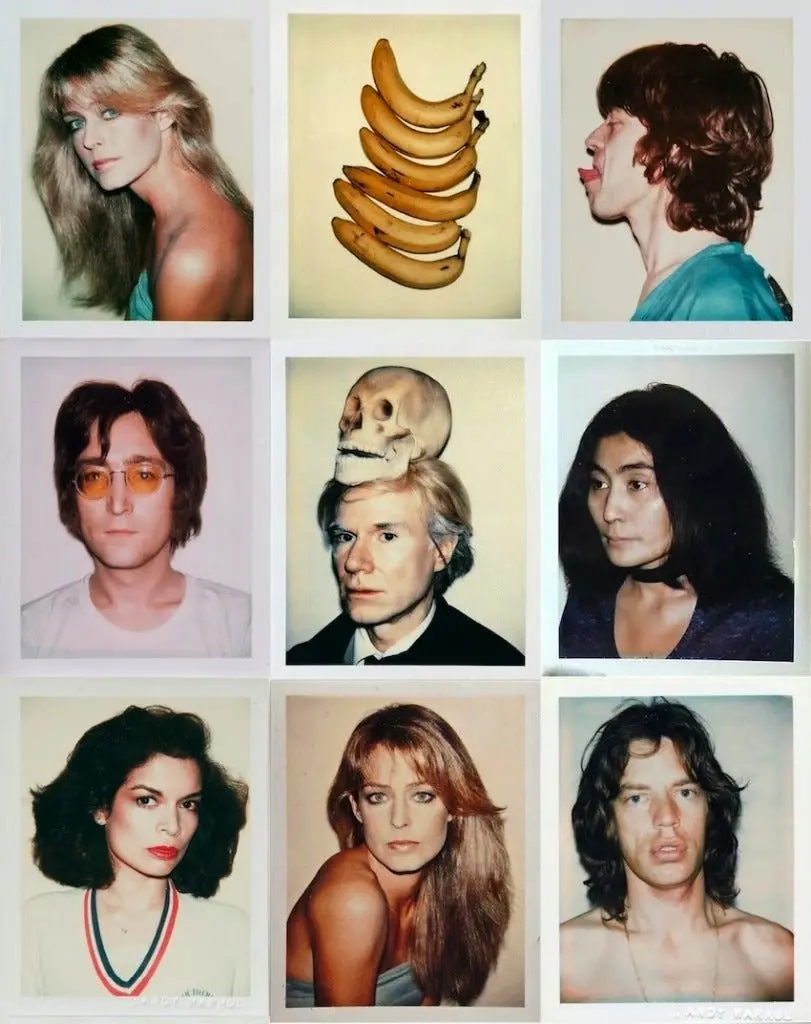

These Polaroid snapshots, crafted by Andy Warhol, capture both the quirky immediacy and raw personality of their famous subjects. Featuring iconic faces like Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and Warhol himself (with skull, no less), these images remind us why Polaroids became so beloved—they offer spontaneous, honest glimpses into the lives of the celebrated and eccentric. Warhol, ever playful, understood that a good portrait is part intimacy, part absurdity, and the instant camera perfectly suited his artistic instincts, making celebrities feel charmingly ordinary, and bananas appear mysteriously profound.

Post-War Photography and Cinematic Innovations (1950s–1970s)

In the post-war era, photography and cinema underwent further dramatic transformations, shaped by rapidly advancing technology, shifting cultural landscapes, and expanding consumerism. With the global turmoil of World War II receding, people worldwide sought stability, prosperity, and avenues to document and celebrate their newfound peace. Photography and cinema enthusiastically filled these desires, evolving to capture the evolving zeitgeist.

Photography became more accessible and pervasive than ever. Companies such as Kodak aggressively marketed affordable cameras and user-friendly film formats to ordinary consumers, enabling virtually anyone to document their daily lives, family milestones, and leisure activities effortlessly. The iconic Kodak Brownie, for instance, brought photography directly into households, turning casual snapshots into cherished family traditions.

The 1950s saw the rise of color photography in consumer markets. Kodak's groundbreaking Kodachrome film became synonymous with vibrant, enduring colors, allowing amateur photographers to produce richly saturated images with ease. Family vacations, birthdays, and backyard barbecues were now captured in vivid color, creating lasting memories that defined a generation.

Polaroid further revolutionized photography in 1948 with instant photography, courtesy of Edwin Land’s (1909–1991) ingenious invention—the Polaroid Land Camera. Instantly producing a physical print within minutes of exposure, Polaroid transformed photography into immediate gratification, predating digital photography's instant-review appeal by decades. Families eagerly adopted Polaroid cameras, relishing the instant joy of holding freshly developed photographs.

Professional photography similarly flourished, driven by sophisticated camera innovations. Single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras, particularly popularized by Japanese brands like Nikon and Canon, offered unprecedented control, precision, and versatility. These cameras quickly became favorites among photojournalists, portrait photographers, and artists, enabling unprecedented creative exploration and documentation.

Photojournalism notably flourished during this period, capturing critical social movements, conflicts, and cultural shifts. Photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) exemplified this era's documentary approach, skillfully capturing decisive moments—fleeting instances encapsulating profound meaning—often using compact, unobtrusive cameras like the Leica to record candid, evocative images. Magnum Photos, a cooperative agency founded by Cartier-Bresson and peers, became synonymous with impactful, socially conscious imagery.

Cinematically, the 1950s witnessed Hollywood confronting an unprecedented threat—television. As TV sets became ubiquitous household fixtures, cinema attendance declined significantly. To counter this, studios developed expansive, immersive cinematic experiences impossible to replicate at home. Technologies like CinemaScope and Cinerama introduced ultra-wide screens, enhancing visual spectacle and immersive storytelling. Films such as "Ben-Hur" (1959) and "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962) epitomized these lavish widescreen epics, mesmerizing audiences with grand scale and opulent production values.

Hollywood also experimented with 3D films, stereophonic sound, and lavish musicals, desperately striving to reclaim audiences from television's allure. Though 3D movies initially proved a short-lived novelty due to cumbersome glasses and gimmicky productions, widescreen and high-quality color films became lasting cinema hallmarks.

Globally, cinema thrived artistically, diversifying through innovative cinematic movements. Italy’s neorealism explored post-war hardships through starkly realistic narratives; directors like Roberto Rossellini (1906–1977) and Vittorio De Sica (1901–1974) masterfully depicted human resilience amidst adversity. France’s influential New Wave movement saw filmmakers such as François Truffaut (1932–1984) and Jean-Luc Godard (1930–2022) experiment boldly with narrative structures, camera techniques, and editing styles, profoundly reshaping cinema's artistic vocabulary.

Japan contributed significantly, with filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa (1910–1998) captivating international audiences through compelling storytelling, profound humanism, and dynamic visual mastery. Kurosawa’s epic samurai films profoundly influenced global cinema, inspiring filmmakers worldwide and cementing Japan's cinematic legacy.

Furthermore, home movie cameras gained popularity among ordinary households, empowering families to document everyday experiences, vacations, and personal celebrations, creating invaluable records of domestic life. Although lacking professional polish, these amateur films offer priceless historical glimpses into everyday lives and experiences, preserved by later digital restoration efforts.

Thus, between the 1950s and 1970s, photography and cinema profoundly evolved, adapting to technological innovations, cultural shifts, and changing consumer preferences. This vibrant era shaped modern visual culture, influencing contemporary media and laying the groundwork for subsequent digital revolutions, forever transforming our relationship with images and storytelling.

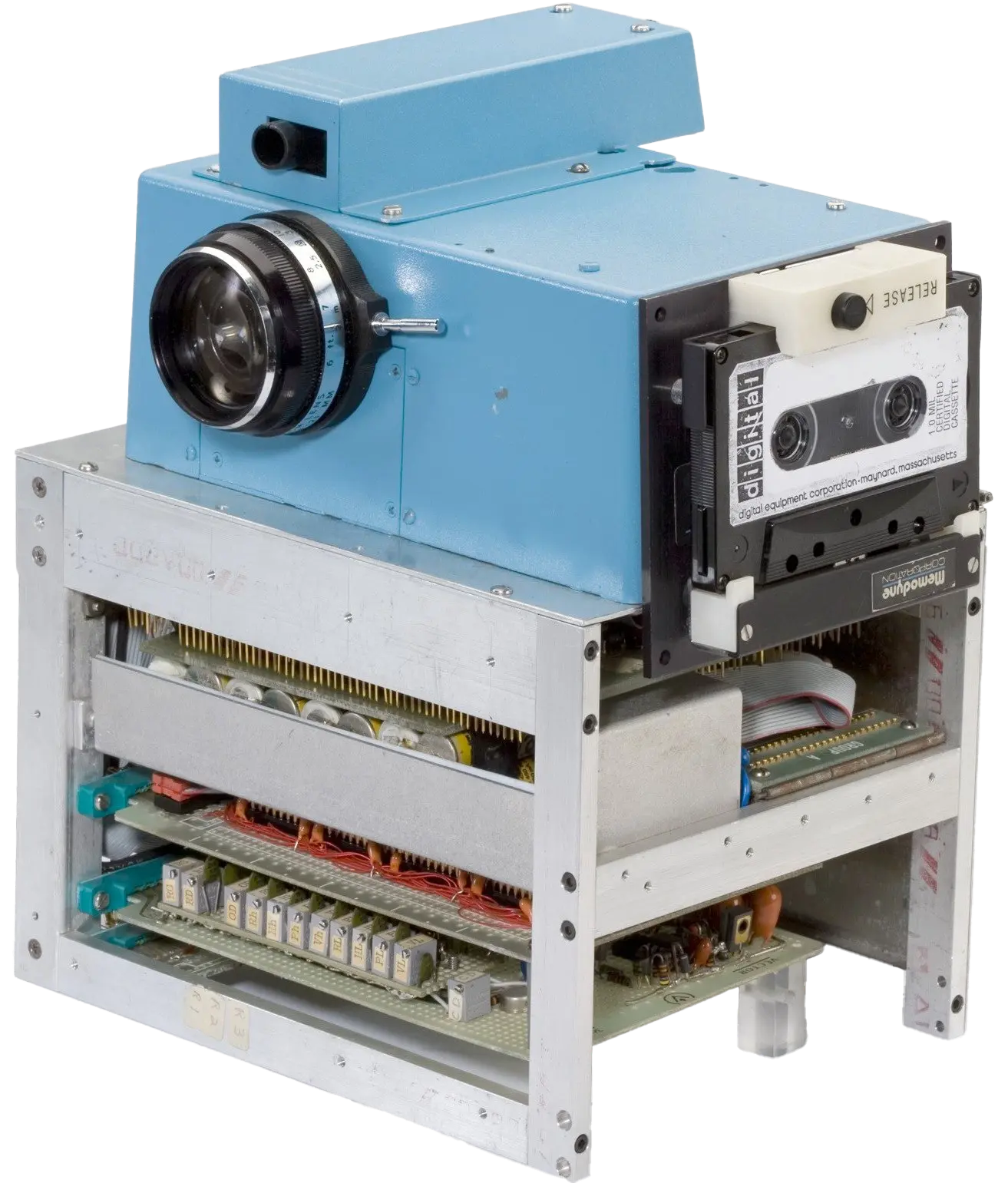

Behold the very first digital camera, built in 1975 by Kodak engineer Steve Sasson—a machine so wonderfully clunky it looks like someone merged a toaster with a VCR and called it a day. This prototype recorded images at a revolutionary 0.01 megapixels and saved them on a cassette tape, which is about as 1970s as you can get without adding shag carpet. Weighing nearly nine pounds and requiring 23 seconds to write a single image, it wasn’t exactly ready for selfies. But it changed everything. Kodak, in a Shakespearean twist, shelved it—afraid it would ruin their film business. It did. Sasson's invention sparked the digital revolution, and this charming blue box became the photographic world's equivalent of a moon landing—if the moon had a rewind button.

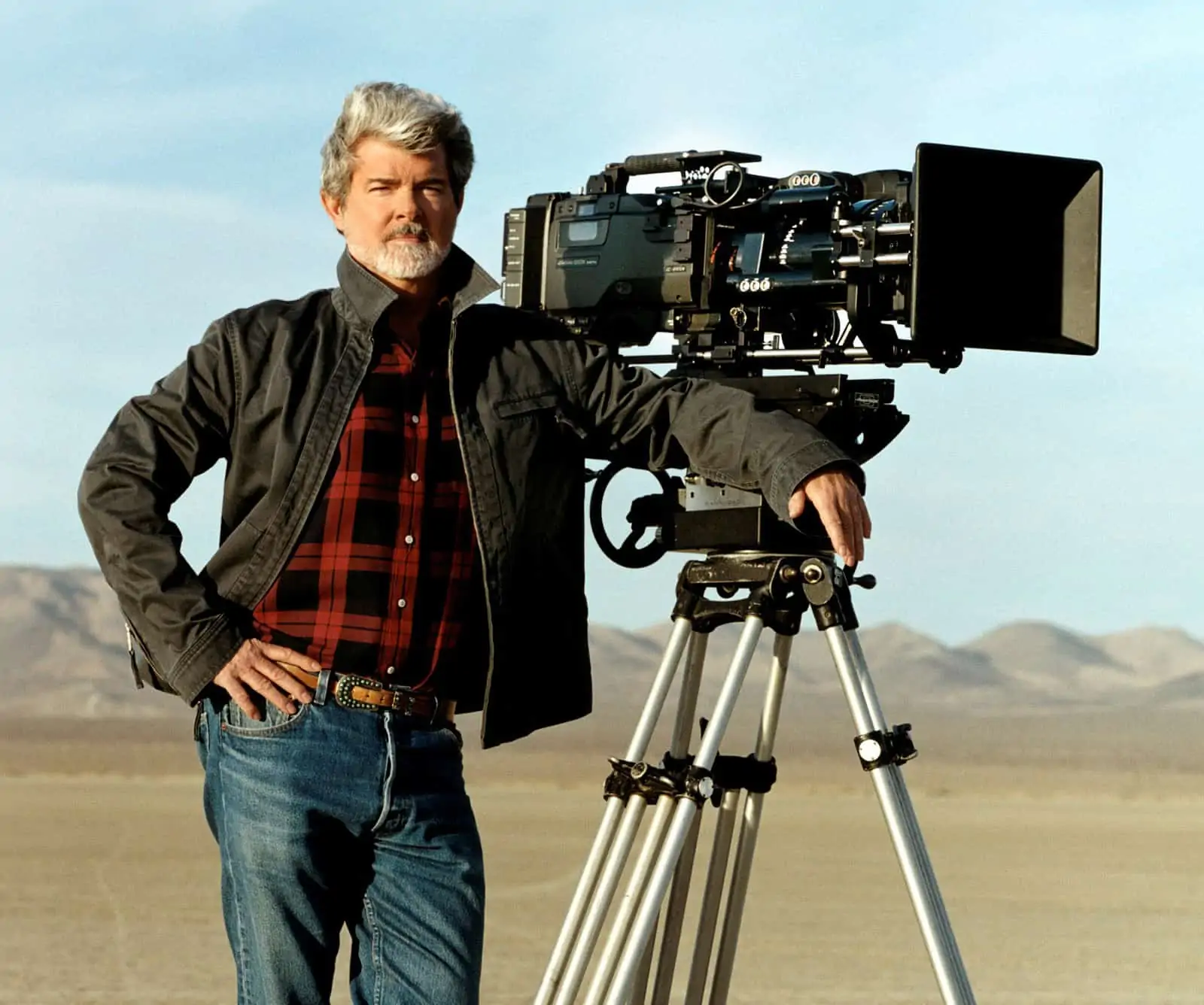

Here we have George Lucas, cinematic Jedi and part-time prophet, standing in a desert beside a digital camera roughly the size of a small refrigerator. This is 2002, and Lucas is mid-revolution—filming Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, the first major blockbuster shot entirely on digital. While most of Hollywood was still debating whether digital could ever rival film (spoiler: it could), Lucas was already in a galaxy far, far ahead. The camera, a Sony HDW-F900, might not look sleek, but it marked the moment celluloid met its match. In typical Lucas fashion, he saw the future, bet big on it, and changed the game—again. That stoic pose? It’s the look of a man who knows he’s already made the Kessel Run in under twelve parsecs.

Here stands Steve Jobs in 2007, looking like a man who just pulled the future out of his pocket and is now deciding whether or not to tell you about it. The device he’s holding—the first iPhone—wasn’t just a phone. It was a camera, a computer, a calendar, a flashlight, a music player, and, eventually, a social life distiller. In one compact rectangle, it quietly obliterated everything from alarm clocks to digital cameras. And speaking of cameras—this tiny thing helped transform photography from a specialized art form into a planetary reflex. Today, thanks to Jobs and this moment, more photos are taken in a single day than in the entire 19th century. Not bad for something that started as “an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator.” And it still made calls… occasionally.

The Digital Revolution: Photography and Film Converge (1980s–Present)

The late 20th century heralded photography and cinema's most radical transformations, as analog methods gave way to digital technologies. This seismic shift dramatically reshaped how images are captured, processed, distributed, and experienced, ushering in unprecedented possibilities, conveniences, and creative opportunities.

In 1975, Kodak engineer Steve Sasson built the world's first digital camera prototype—a bulky, toaster-sized contraption capable of capturing grainy black-and-white images stored on cassette tapes. Although crude by today's standards, Sasson's pioneering invention foreshadowed photography's impending digital metamorphosis, forever altering the medium's trajectory.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, digital imaging technologies rapidly advanced, becoming increasingly practical and accessible. Early digital cameras, initially costly and producing limited-resolution images, steadily improved through relentless innovation. Manufacturers like Canon, Nikon, and Sony competed fiercely, introducing consumer-friendly cameras boasting enhanced sensors, increased resolutions, and intuitive interfaces.

The advent of affordable, high-quality digital cameras empowered amateur photographers enormously. Without the constraints of film costs or processing delays, individuals experimented freely, capturing countless images instantly reviewable, editable, and shareable. Digital photography swiftly permeated daily life, transforming personal documentation, communication, and artistic expression.

Smartphones emerged as photography's most disruptive innovation, combining compact, high-quality cameras seamlessly integrated into versatile, portable devices. Apple's release of the iPhone in 2007 revolutionized mobile photography, profoundly democratizing image creation. With powerful cameras perpetually available in users' pockets, spontaneous photography flourished exponentially. Social media platforms, especially Instagram, emerged concurrently, facilitating instant global image sharing and radically reshaping visual culture and communication.

Professionally, digital photography offered extraordinary creative possibilities and efficiencies. Photojournalists appreciated instant image transmission capabilities, accelerating news dissemination dramatically. Commercial and studio photographers embraced digital’s rapid workflow advantages—immediate image review, precise adjustments, extensive editing possibilities, and efficient client interactions. Digital imaging also revitalized fine-art photography, enabling innovative techniques, compositing, and experimentation previously inconceivable.

Cinema experienced an equally profound digital revolution. Initially impacting film post-production and special effects, digital technologies enabled unprecedented visual storytelling possibilities. Landmark films like "Jurassic Park" (1993) demonstrated computer-generated imagery's (CGI) staggering potential, vividly depicting lifelike dinosaurs alongside actors convincingly. CGI rapidly became cinema's indispensable tool, facilitating complex visual effects, imaginative world-building, and compelling character creations previously unattainable practically.

Digital filmmaking technology advanced significantly by the early 2000s, culminating in practical, high-definition digital cinematography solutions. George Lucas notably embraced digital cameras extensively during "Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones" (2002), becoming the first major Hollywood film shot entirely digitally. Subsequently, filmmakers like James Cameron with "Avatar" (2009) showcased digital's limitless creative potential, employing groundbreaking 3D digital cinematography and motion-capture technologies, offering audiences immersive, visually dazzling experiences.

Digital projection rapidly supplanted traditional celluloid reels in cinemas globally, streamlining film distribution and presentation. Digital cinema eliminated costly film printing, transportation logistics, and deterioration issues, facilitating consistent high-quality presentations worldwide. Meanwhile, digital editing revolutionized post-production processes, enhancing precision, flexibility, and creative potential significantly.

Simultaneously, digital technology profoundly impacted animation. Pixar's "Toy Story" (1995) famously became the first fully computer-animated feature film, heralding digital animation's boundless potential. Pixar and subsequent studios like DreamWorks harnessed digital animation's creative freedom, crafting imaginative, visually spectacular animated films universally beloved.

The internet further transformed cinema's consumption and distribution. Streaming services, notably Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+, revolutionized content accessibility, fundamentally reshaping viewing habits. Audiences increasingly embraced home viewing conveniences, prompting studios to reconsider traditional theatrical release strategies, distribution models, and content creation approaches.

Thus, photography and cinema's digital revolution comprehensively transformed visual media—democratizing image-making, expanding creative possibilities, enhancing accessibility, and profoundly reshaping global culture. Today, digital convergence continues shaping visual storytelling's future, blending photography and cinema seamlessly, innovating continuously, and transforming profoundly how humanity captures, experiences, and communicates through images.

Conclusion: Reflecting on Photography and Cinema's Enduring Legacy

As we reflect on the incredible journey of photography and cinema—from humble pinhole projections and ghostly pewter plates to the mesmerizing clarity of digital imagery and the universal accessibility of smartphones—it's clear that these mediums have profoundly reshaped human experience. They have influenced how we document history, perceive reality, and communicate stories across generations and cultures.

Photography and cinema, born from curiosity and innovation, have continually adapted and evolved in response to humanity’s relentless desire to capture, share, and immortalize moments. Each technological leap forward has not only expanded creative possibilities but also democratized the act of visual storytelling, empowering more people than ever to participate in crafting narratives that shape our collective consciousness.

Yet, beyond technological marvels and artistic achievements, photography and cinema have played deeply personal roles in our lives. They serve as visual anchors, preserving memories, sparking emotions, and connecting us to our pasts and futures. Each snapshot and frame contains countless stories—stories of joy, sorrow, triumph, and resilience—captured in fractions of a second yet resonating profoundly across lifetimes.

In a rapidly changing world, the enduring power of images remains a constant force, capable of transcending barriers of language, culture, and time. Photography and cinema continue to offer windows into diverse human experiences, enabling empathy, understanding, and shared connections among billions worldwide.

As we look forward, photography and cinema’s future promises continued innovation and boundless creativity, driven by ever-advancing technologies and humanity’s enduring passion for storytelling. At Photobalm, we celebrate this vibrant legacy, committed to preserving, restoring, and enhancing these cherished visual narratives, ensuring they inspire and enlighten future generations.

Thus, the journey continues—filled with endless possibilities, captivating stories, and extraordinary moments waiting to be captured. The remarkable evolution of photography and cinema is far from over; indeed, it may have only just begun.